One of the things Sweetheart was known for was her art. As she did with her family, she not only took her art very seriously, but she took it to another level. As with most things in her life, Sweetheart didn’t take so much as pride in what she did, but she was deliberate with it.

The Meaning of Art

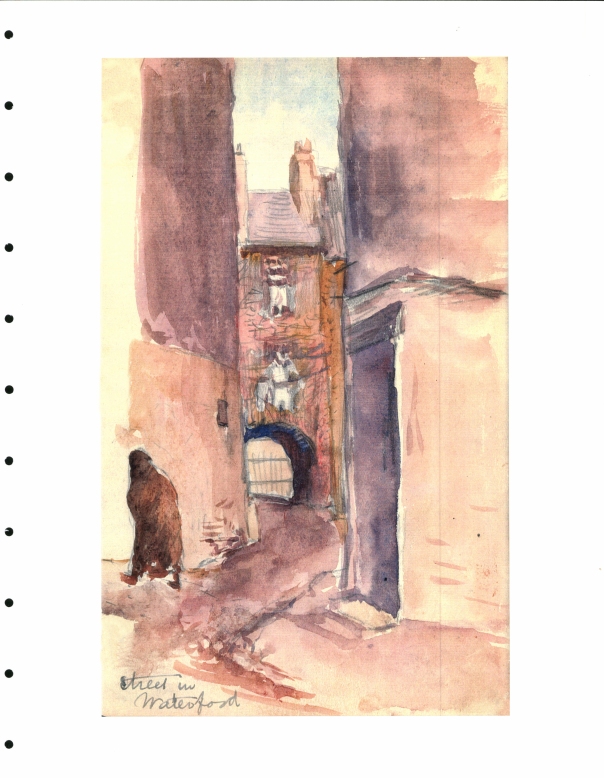

Sweetheart never went to art school, or had much of any professional training as far as I know, though she was always eager to talk to artists if she could. But drawing and painting flowed through her veins, they rippled from her. She painted the way other people talk, as part of her everyday life. On her wedding trip in far western Canada, when she was 28, she was always sketching animals, children, the guides, the boatmen, not to create a portfolio, but the way she wrote of them in her diary — to set down her impressions. When she cruised round the world at 75, she was sketching the captain, the cooks, the cliffs they passed maybe in the early dawn, temple dancers, market women. She grew sketches as an apple tree grows apples. When she had her family in Toronto she would toss off place cards at table with comical sketches and verses. She made a “funny paper,” the Weekly Goosh, to tell absent members what was going on. This was not “art for art’s sake” — nothing so pretentious — but art for the sake of family fun.

Yet she also thought of painting as a very serious undertaking, in the service of truth, even sometimes a “higher” truth than that of appearances. When she painted a portrait she would start with the eyes, and then hang the face from them. Therefore the eyes in the finished picture would be strong, dark, almost burning. There is an unfinished portrait in the book (p. 228) which is almost nothing but eyes. That is, the rest of the face is there, but sketched in — it is the eyes which are finished, which dominate, which gaze at you. She would give her subjects a “soulful” look, something looking out through the eyes which someone just looking at the person might not see at all. Even a flight of old stone steps, or a bougainvillea bush, could radiate a sense of inner life, almost a spiritual essence that the casual eye would not see, that it was the painting’s chief purpose to bring out. Watercolor worked better for this than oils, because it seems to let the light through.

She had excellent control of the watercolor brush. Of course it was also the only medium she could carry with her and set up in a market place. She did sometimes paint in oils, but watercolor suited her. Water color is light and luminous and gave a deceptive impression of frailty — almost of unimportance, as if it were just a quick sketch which could be thrown away. We did not throw them away of course, but we gathered stacks of sketchbooks which still lie on shelves somewhere and may never see daylight again, except for those in this book. She did do finished paintings when she could, and they too, like the sketches, have a “momentary” quality — a sense of capturing or recording a moment, and of themselves also being momentary — quick, fleeting, and alive.

She had excellent control of the watercolor brush. Of course it was also the only medium she could carry with her and set up in a market place. She did sometimes paint in oils, but watercolor suited her. Water color is light and luminous and gave a deceptive impression of frailty — almost of unimportance, as if it were just a quick sketch which could be thrown away. We did not throw them away of course, but we gathered stacks of sketchbooks which still lie on shelves somewhere and may never see daylight again, except for those in this book. She did do finished paintings when she could, and they too, like the sketches, have a “momentary” quality — a sense of capturing or recording a moment, and of themselves also being momentary — quick, fleeting, and alive.

Related articles

- Watercolor sketching in the park. (smudgemaster.wordpress.com)

- What Family Means According to Sweetheart